There you go.

Good morning.

I was wondering how to start today. I was considering the title of the panel, “Sexuality and Phantasy”, and struggled to think. What, if anything, could I add to the subject?

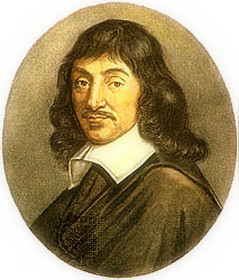

I realised this. I realised that whenever I find myself thinking about Sexuality, I find myself thinking of Descartes --you know, René Descartes, the philosopher.

Of course Descartes did not, as far as I know, write about sexuality as such --or about phantasy for that matter. But he did write about the mind-body problem.

This will be my starting point today.

Descartes had observed something, which struck him as really very important. He had observed that there is a difference between material things, things that have proper dimensions --such as length, height and so on-- and immaterial things that do not have dimensions, such as the ones that you have in your mind. He called the former extended things or “res extensae” (res extensa in singular); he called the latter thinking things or “res cogitantes” (res cogitans in singular). Descartes believed that these two kinds of things although so very different, they can come together. They come together in the only being that has both a (material) body and a (non-material) mind: the human being. Descartes thought that the human being is the only extended thing that also has the quality of a thinking thing.

There are practical questions of course. How is this possible? How can these two qualities co-exist in one and the same being? Descartes thought about it and believed that he identified the place where the one meets the other. It was somewhere in the skull, underneath the brain. There is a gland there which was known from the ancient times to be the seat of vital fluids. It was called “pineal gland”, because it looks like a pine-nut. Today we know that the pineal gland is the seat of many hormones, very important for the regulation of many subsystems of the organism. Descartes did not know about hormones. But he believed that the pineal gland is really the one place in the human being where res cogitans and res extensa meet.

Descartes had a theory of behaviour which involved what he called passions. He had named six passions: wonder, love, hate, desire, joy and sadness. So, he hypothesised that the pineal gland was the important place where passions meet the body.

You may be asking yourselves right now, how is this relevant to today’s conference? How is Descartes’s theory relevant to today’s understanding of these questions? Who, but the endocrinologists, cares about the pineal gland today? Nobody.

This might be true; in general we do not seem to think very much about the pineal gland anymore. But Descartes’s ideas on the subject have left a trace. Let me bring an example. It’s a bit unexpected. It’s a film.

“The Matrix”.

You may recall the story of the film: unbeknownst to them, people were living their lives in a gigantic computer simulation, called the Matrix. Inside the simulation things were “smooth” and seamless. You could not see that you were in a simulation unless you were “in the know”. The real people, the ones who were disconnected from the simulation, had a connecting interface there at the back of their skull. Think of it as a plug. In order to re-connect to the simulation you had to put a probe in this plug. The film spared the details, but the placement of this connector and the length of the probe were hinting at one thing. They were hinting at the pineal gland. In a possible gesture to Descartes, the writers of “Matrix” imagined the pineal gland as the interface between the human body and the giant computer servers that hosted the Matrix. This interface allowed the exchange of messages and the communication of the simulated world, as constructed by the computers, with the body of the person who was logged into the simulation. The pineal gland was the meeting point of the human body and the computer’s “mind”.

I am not going to spoil for you the story of the film here. It’s quite entertaining and thought provoking, and if you have not watched it, please do.

Let me try, instead, to bring all this in connection to today’s subject.

I will start with an observation.

Here it is:

People do not know what to do with their bodies.

That’s all.

Sounds funny --I have to admit, I did want it to sound funny-- but it is not funny at all. It’s an observation.

First and foremost it is a clinical observation. You see this in the clinic: anorexia; bulimia; body dysmorphic disorder; gender dysphoria; low self-esteem; insecurity; anxiety; panic attacks; and so on and so forth. Each and every manifestation of human suffering has something to do with the body.

People do not know what to do with their body, and they suffer because of this.

One sees it on the street: You see body-builders; you see super-models; you see bankers dressed perfectly; you see hipsters; you see psychoanalysts; on the street you see all kinds of people. Always the same old story.

People do not know what to do with their body. It confuses them, it causes them discomfort.

Here you go: Each and every manifestation of human life reflects this very same discomfort with the body.

Of course everybody has a body. The cat has a body; the dog has a body; the mouse has a body. Do they all suffer because of their having bodies?

No. In contrast to all other animals, humans have to say something about their body, they have to think about it, they have to include, both their body and the knowledge that they have one, in their understanding of the world. Humans have to settle for the fact that they have a body, that they know it, and that they do not know what to do with it.

In other words, the one thing that is different with humans, different from every cat or dog or mouse, is that humans are concerned about their body. Or, inversely, that their body concerns them.

By the way, you might recognise in what I am saying Heidegger’s fundamental insight. Heidegger described the human being as that kind of being that is concerned about Being --his or her own Being, or Being in general. That’s not a coincidence. Heidegger did not speak a lot about the body, specifically, but in his thought the question of the body is evident.

Having a body and having to do something about it, or with it, is the biggest drama, if you allow me the exaggeration, of the human condition. And the biggest challenge for philosophy.

Descartes tried to settle all questions with his mind-body ontology. He was of course aware that many more questions remained. He understood, for example, that in order for it to be possible to have a mind, or to have a body, you would need to have some kind of external reference point, a third pole. He introduced a third type of thing, which he called res divina, divine thing. This divine thing, of which only one instance exists --God-- was in Descartes’s view, a guarantor, of sorts, of the connection between the thinking thing and the extended thing.

An embarrassing complication for Descartes’s theory was sexuality. As I mentioned earlier, Descartes had a theory of passions. Obviously these passions had something to do with the mind-body connection. There were issues of management and control. For Descartes, the real challenge for the human being was to devise and implement rules that would allow him or her, the human being, to master their passions and avoid becoming their prey. Clearly, to control passions meant also to control sexuality. In his time of modesty, sexuality was an embarrassment for Descartes.

In fact, the same embarrassment would accompany everybody who has ever tried to think and talk about sexuality --not only then, in those times of modesty, even today. Today modesty has been reversed to the opposite, to a kind of imperative to enjoy and have a nice time: you have sexuality; you must not ignore it; you must enjoy yourself. This is the same old embarrassment of sexuality, turned upside down.

Studying history, looking at societies and all different institutions in a society, looking at their origins and their development, one can see that most, if not all, of them have at least at some level, at least in some aspect something to do with this very same embarrassment.

Take matriarchy, for example. Matriarchy stems from, and revolves around, the fact that women have sex and procreate. Take patriarchy. It revolves around the fact that men also have something to do with sex and procreation. In human societies the biology of sex becomes subordinated to the meanings we assign to its manifestations and procedures. Almost all institutions in human societies stem from an understanding of the sexual life of the human being –i.e. from an inclusion into a discourse of a biological fact. If you need more example, think of institutions such as the women-men segregation or the regulation of sex according to your religious beliefs, of in connection to your marital status, and so on, and so forth. All these are institutions designed to control and restrain and, actually, sooth the discomfort and embarrassment of sexuality --designed, in other words, to help people to deal with this embarrassment of having a body.

One would think that even the Oedipus complex is, in its core, a manifestation of this embarrassment.

It is important to remember, however, that the embarrassment I am talking about has nothing to do with the biology of sex. It has to do with sexuality, i.e. with our understanding of sex. Or, to put it more accurately, it has to do with the way the biology of sex enters into our discourse. To use slightly more technical Lacanian terms, I would say that sex is in the Real, whereas sexuality is in discourse, i.e. the Symbolic. This is how I understand this famous Lacan adage, “There is no such a thing as a sexual rapport”.

The domain of sexual rapport is discourse, and not biology. After all people still do have sex.

If the body is the question, what about the mind?

Freud in his writings did not use the word “mind”; he preferred to use the term “psyche”, or “mental apparatus”.

Lacan, on the other hand, chose to speak of a “web of signifiers”.

It is tempting to say that Descartes’s “thinking thing” is something not very dissimilar to a web of signifiers. In fact, it seems to me that all these terms, “psyche”, the “mind”, the “thinking thing”, are equivalent. They are names given to, and representations of, one’s personal web of signifiers.

(“Personal”, because it comes from your own personal history.)

So, what is one to do with this? With the web of signifiers I mean.

One thing you could do, since you are in discourse, is you can use it to make a description of yourself. This is what we call “phantasy”. A phantasy is first and foremost a description of yourself.

The most basic version of this description of yourself is the so called “fundamental” phantasy. One’s own fundamental phantasy, is, as the name implies, private and indeed fundamental. You do not see it out in the open. You infer it in psychoanalytic practice.

A fundamental phantasy is a sentence in language, it’s a sentence that you have formed using words that you have heard. It’s a sentence that comes from outside.

This is how a fundamental phantasy looks like:

“I have always been my mother’s favourite”.

Or: “In school nobody played with me”.

Or: “I am destined for success”.

Or: “I do not believe that people can love me”.

Or: “A child is being beaten”.

This last example of a fundamental phantasy is a bit tricky. You recognise it perhaps. “A child is being beaten” was the title of a 1919 paper by Freud. In it he described a personal phantasy which, intriguingly, was not about the person who had it. Being a phantasy, it reflected and represented something: it was not a description of a fact --say for example that somewhere, someone was being beaten. Freud helped us see the transformations that this phantasy had gone through. He showed us how, in this particular case, this phantasy was an evocation of love. Or, rather, a declaration, or expectation of love: Someone loves me. That child is being beaten, whereas my father loves me. Or something like this.

One could take it a step further: Instead of “a child being beaten” what the phantasy really says is: “I love to be beaten”. And thus, perhaps surprisingly, the fundamental phantasy would meet sexuality. Because when my phantasy says, “I love to be beaten”, my phantasy is becoming a sexual phantasy.

One could generalize here. It is almost always the case that a fundamental phantasy, in some disguised way, is also a sexual phantasy.

Indeed I would say this:

The fundamental phantasy serves as a blue-print of the basic structure of each and every one the sexual relationships that we are able to engage in.

In other words, the fundamental phantasy is a blue-print of the way we have negotiated the fact that we have a body.

It is in this way that the connection between sexuality and fundamental phantasy represents, in my view at least, a new version of the mind-body problem. Of course, in this new, updated version, we are not any more interested in the pineal gland and the fluids it controls.

Instead, we are now focusing on the whole body. And instead of fluids controlled by the pineal gland, we are focusing on the jouissance of the body. And we no longer need the Divine thing to give us reference points. We now postulate the Symbolic order and refer to the Big Other. Our personal web of signifiers, our psyche, obtains its self-consistency via the Big Other. (At least for people in discourse.)

What does this all tell us? Are we all Cartesian? Is Lacan’s theory a Cartesian one? Is this what I am trying to articulate here?

No, not really. My point was not to represent Lacan as a Cartesian.

What I wanted to show, the main point I have been trying to make today, is simply this: Descartes, as well as Lacan, as well as everybody else, all of them really, have tried to get in terms with one major, and uniquely human, problem.

The problem of having a body.

Thank you

There is a problem, I think, in characterising the mind as opposite of the body in the sense of “res extensa” because in psychoanalysis the mind is “res extensa” too.

CT: Perhaps so. But in any case I am not trying to follow Descartes here. I wanted to point out that he tries to solve the same problem as everybody else, namely the problem of the body. Heidegger too tries to solve the same problem, even though he speaks very little about the body. And then Psychoanalysis too tries to speak about the same problem.

I could add something, if you allow me, just in connection to this: One major difference between the original Cartesian ontology and the “updated” ontology that I tried to present here is that the “mind”, the “thinking thing” of Descartes is thought to be self-contained, autonomous, and independent of the body. In Descartes, the mind meets the body. In contrast, when I speak about a personal “web of signifiers” I recognise that this cannot exist without the body. It is in the body, in the sense of signifierised jouissance, but its origin is elsewhere, it is outside, in the world. In other words, the web of signifiers is not on the same ontological level with the body: it’s on a meta-level, so to speak. Their type of existence is different, their ontological status is different.

Thank you.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed